Beards and facial hair can be attractive — it depends what you want from a relationship.

Women judge fully bearded men to be a better bet for long-term relationships, one study finds.

This might be because it makes men look more ‘formidable’.

Certainly, beards make men look older and more aggressive.

Beards are also often judged to make men look like they have higher social status.

However, for short-term relationships, women judge stubble to be most attractive, the research found.

Are beards really attractive?

However, whether or not beards are attractive to women is a big area of controversy in beard-related psychological research.

Some studies find that bearded men are more attractive to women than the clean-shaven, others not (e.g. Reed & Blunk, 1990; Muscarella & Cunningham, 1996).

The most recent research goes against both beards and being clean-shaven and is starting to show the benefits of stubble.

But do women prefer light stubble or heavy stubble?

The jury is still out, with one study suggesting light stubble (Neave & Shields, 2008) and another heavy stubble (Dixson & Brooks, 2013).

Facial hair study details

The study showed pictures of men with different levels of facial hair to over 8,000 women.

Men’s faces were also ‘masculinised’ and ‘feminised’ by computer manipulation to see what effect this would have.

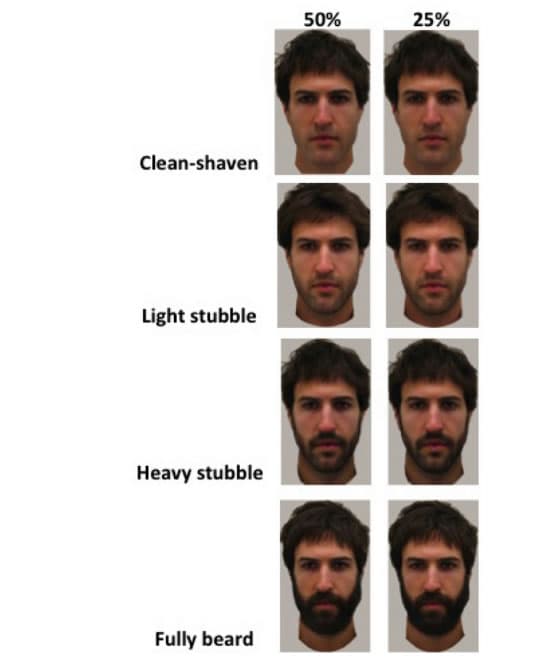

Here is an example of the feminised male faces along with different beard growths:

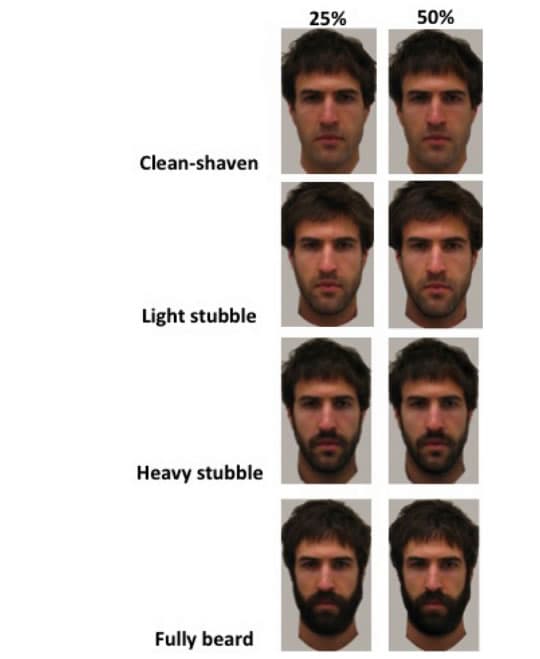

Here are the masculinised faces with different beard lengths:

The results showed that the more faces were masculinised or feminised, the less attractive they were.

Stubble is attractive

Stubble was most attractive to women in a short-term context and full beards most attractive when considering a long-term relationship.

The study’s authors explain:

“…beards may be more attractive to women when considering long-term than short-term relationships as they indicate a male’s ability to successfully compete socially with other males for resources.

Interestingly, a longitudinal analysis of men’s facial hair fashions in London from 1871 to 1972 revealed that beards became more common when the marriage market was more male-biased and the degree of intrasexual competition to attract mates was augmented.”

Beards and facial hair not universally attractive

Remember that all these are ‘average’ findings across thousands of people.

There are, obviously, both beard-lovers and beard-haters out there.

The study is the latest in a long and illustrious line of important beard-related research.

Not all studies agree on whether beards are more attractive, although stubble does seem to be emerging as a strong favourite, especially for shorter term relationships.

The study was published in the Journal of Evolutionary Biology (Dixson et al., 2016).