Another reason why changing habits is tougher than it seems.

Keep reading with a Membership

• Read members-only articles

• Adverts removed

• Cancel at any time

• 14 day money-back guarantee for new members

Another reason why changing habits is tougher than it seems.

Struggling with new habits? The timing could be wrong.

‘Boosting’ could help governments tackle obesity, pollution by encouraging people to change their own behaviour.

There is one thing that you need to develop an exercise habit that sticks that many people inexplicably discount.

There is one thing that you need to develop an exercise habit that sticks that many people inexplicably discount.

Exercise is a difficult habit to pick up.

It is not enough just to set aside a particular period in the day and rely on willpower to follow through.

Part of the reason is that people don’t necessarily start exercising because they enjoy it.

Instead, they start exercising to lose weight or look better.

When the changes are minimal, or not what they had hoped for, then it is easy to give up.

Research finds that one key to getting the exercise habit is tapping in to intrinsic rewards.

Intrinsic rewards are things like the pleasure we get from the activity itself.

This could be through socialising with others, the endorphin rush, or something else.

When intrinsic, internal rewards are linked up with a particular, regular slot in the day for exercising, then the habit can flourish in the long term.

Finding the missing key, then, is all about identifying those highly personal intrinsic rewards.

What is it about the exercise that makes you feel good?

If the answer is nothing, then it is time to think about different types of exercise that do make you feel good.

For example, gyms are not for everyone, some people prefer to play sports in teams, others prefer exercising alone.

Some people like rigid goals and structure, others prefer a more free-form approach.

Find your pleasure and the habit is much more likely to stick.

Dr Alison Phillips, who led the research, said:

“If someone doesn’t like to exercise it’s always going to take convincing.

People are more likely to stick with exercise if they don’t have to deliberate about whether or not to do it.

If exercise is not habit, then it’s effortful and takes resources from other things you might also want to be doing.

That’s why people give it up.”

The study was published in the journal Sport, Exercise and Performance Psychology (Phillips et al., 2016).

How sleepiness transforms your habitual behaviours.

Forming a habit takes an average of 66 days, but it depends on the habit and how you build it.

Forming a habit takes an average of 66 days, but it depends on the habit and how you build it.

Say you want to build a new habit, whether it’s taking more exercise, eating more healthily or writing a blog post every day, how long does it need to be performed before it no longer requires Herculean self-control?

Clearly it’s going to depend on the type of habit you’re trying to build and how single-minded you are in pursuing your goal.

But are there any general guidelines for how long it takes to form a habit before behaviours become automatic?

Ask Google a few years ago and you used to get a figure of somewhere between 21 and 28 days.

In fact, there’s no solid evidence for this number at all.

The 21-day myth for how long to form a habit may well come from a book published in 1960 by a plastic surgeon.

Dr Maxwell Maltz noticed that amputees took, on average, 21 days to adjust to the loss of a limb and he argued that people take 21 days to adjust to any major life changes.

Unless you’re in the habit of sawing off your own arm, this is not particularly relevant.

Psychological research on this question is available, though, in a paper published in the European Journal of Social Psychology.

Phillippa Lally and colleagues from University College London recruited 96 people who were interested in forming a new habit such as eating a piece of fruit with lunch or doing a 15-minute run each day Lally et al. (2009).

Participants were then asked daily how automatic their chosen habits felt.

These questions included things like whether the potential habit was ‘hard not to do’ and could be done ‘without thinking’.

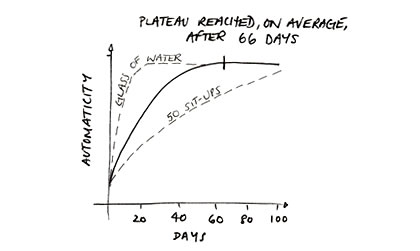

When the researchers examined the different habits, many of the participants showed a curved relationship between practice and automaticity of the form depicted below (solid line).

On average, a plateau in automaticity was reached after 66 days.

In other words, it had become as much of a habit as it was ever going to become.

This graph shows that early practice was rewarded with greater increases in automaticity and gains tailed off as participants reached their maximum automaticity for that behaviour.

Although the average was 66 days, there was marked variation in how long habits took to form, anywhere from 18 days up to 254 days in the habits examined in this study.

As you’d imagine, drinking a daily glass of water became automatic very quickly but doing 50 sit-ups before breakfast required more dedication (above, dotted lines).

The researchers also noted that:

What this study reveals is that when we want to form a relatively simple habit like eating a piece of fruit each day or taking a 10 minute walk, it could take us over two months of daily repetitions before the behaviour becomes a habit.

And, while this research suggests that skipping single days isn’t detrimental in the long-term, it’s those early repetitions that give us the greatest boost in automaticity.

Unfortunately it seems there’s no such thing as small change: the much-repeated 21 days to form a habit is a considerable underestimation unless your only goal in life is drinking glasses of water.

While habits can have a strong influence on behaviour, they are frequently misunderstood and far from unbreakable.

Governments, businesses and psychologists waste untold effort on behaviour change tactics that are mostly ineffective — here are the three that really work.

How to still look good if you are one of the two-thirds of people who give up on their New Year’s resolutions within a month.

How much are habits a product of what we want versus what we habitually do?

How much are habits a product of what we want versus what we habitually do?

Simple repetition is the key to hacking your brain to form solid habits, research concludes.

Just find a way to keep repeating the same action until it sticks.

It doesn’t matter whether the action provides you satisfaction or not — repetition is all.

At least, that is the message from a mathematical model of habit formation developed by psychologists at Warwick, Princeton and Brown Universities.

Dr Elliot Ludvig, study co-author, said:

“Much of what we do is driven by habits, yet how habits are learned and formed is still somewhat mysterious.

Our work sheds new light on this question by building a mathematical model of how simple repetition can lead to the types of habits we see in people and other creatures. “

The researchers created a computational model that involved digital mice pressing levers to get a reward.

The simulation showed that after training, mice will continue to press a lever even after it stops rewarding them.

In other words, the digital mice kept doing something they had done before, despite receiving no reward.

The habit continues, despite having lost all value.

While mice are clearly different to human beings, repetition has surprising power over us all.

The next step for the researchers is to test their model on humans.

Dr Amitai Shenhav, study co-author, said:

“Psychologists have been trying to understand what drives our habits for over a century, and one of the recurring questions is how much habits are a product of what we want versus what we do.

Our model helps to answer that by suggesting that habits themselves are a product of our previous actions, but in certain situations those habits can be supplanted by our desire to get the best outcome.”

The study was published in the journal Psychological Review (Miller et al., 2018).

Join the free PsyBlog mailing list. No spam, ever.