The unexpected negative effect of positive thinking on mental health.

Keep reading with a Membership

• Read members-only articles

• Adverts removed

• Cancel at any time

• 14 day money-back guarantee for new members

The unexpected negative effect of positive thinking on mental health.

The mental advantage of sitting around and doing nothing much.

Distant deadlines appear to reduce the sense of urgency since people interpret the date as meaning the task does not matter.

Fruits and vegetables boost happiness even quicker than health.

Fruits and vegetables boost happiness even quicker than health.

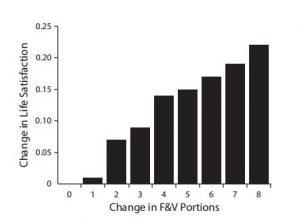

Eating 8 portions of fruit and vegetables a day provides the maximum boost to people’s happiness, a study finds.

The positive effect comes faster than the boost to health.

Up to 8 portions, the more portions people ate, the happier they were.

The effect on happiness of eating those 8 portions compared with none was dramatic.

In terms of life satisfaction, it was equivalent to the difference between being employed and unemployed.

The graph below shows the increase in life satisfaction with portions of fruit and vegetables consumed each day.

Graph courtesy of Mujcic & Oswald (2016)

It is the first time a large study has found that fruit and vegetables contribute to happiness on top of their well-known protective effect against cancer and heart disease.

Professor Andrew Oswald, one of the study’s authors, said:

“Eating fruit and vegetables apparently boosts our happiness far more quickly than it improves human health.

People’s motivation to eat healthy food is weakened by the fact that physical-health benefits, such as protecting against cancer, accrue decades later.

However, well-being improvements from increased consumption of fruit and vegetables are closer to immediate.”

The conclusions come from following over 12,000 people.

Participants kept food diaries and their psychological well-being was measured.

Within two years, those eating more fruits and vegetables felt better, the results showed.

Dr Redzo Mujcic, one of the study’s authors, said:

“Perhaps our results will be more effective than traditional messages in convincing people to have a healthy diet.

There is a psychological payoff now from fruit and vegetables — not just a lower health risk decades later.”

One possible mechanism by which fruit and vegetables affect happiness is through antioxidants.

There is a suggested connection between antioxidants and optimism.

And, if you need more encouragement:

The study was published in the American Journal of Public Health (Mujcic & Oswald, 2016).

Thomas Edison was famous for failing over 1,000 times when trying to create the light bulb.

Study tested how people feel 90 minutes after watching a tearjerking film.

Study tested how people feel 90 minutes after watching a tearjerking film.

People who watched a sad film were eventually in a better mood after watching it than they were before, a recent study found.

However, it took about 90 minutes, on average, to feel better after crying.

The research could help explain the function of crying.

Some argue that crying provides emotional relief.

And yet, when it is measured in the lab, crying makes people feel much worse.

The study showed 60 people two films known to be tearjerkers.

Their mood was measured right after watching the films, then after 20 minutes and 90 minutes.

Around half of the participants cried during the film: naturally they felt worse immediately afterwards.

The results showed, though, that after 20 minutes the criers had recovered their initial dip in mood.

It is probably this dip and then recovery that makes people feel that crying has improved their mood.

However, after another 60 minutes the criers felt even happier than they did before watching the films.

None of the mood shifts were related to how much people cried.

Asmir Gračanin, the study’s lead author, said:

“After the initial deterioration of mood following crying, it takes some time for the mood not only to recover but also to be lifted above the levels at which it had been before the emotional event.”

Talking of crying, here is another strange finding about happiness and crying:

https://www.spring.org.uk/2014/11/the-reason-overwhelming-happiness-makes-people-cry.php

The study was published in the journal Motivation and Emotion (Gračanin et al., 2016).

Watching film image from Shutterstock

Not all daydreaming is bad for focused thinking, new study finds.

Not all daydreaming is bad for focused thinking, new study finds.

Daydreaming and mind-wandering can have positive effects on mental performance in the right circumstances, a new study finds.

It used to be thought that when people are trying to solve puzzles, they perform best when the mind wandering part of the brain — called the ‘default network’ — is relatively inactive.

This makes sense given that ‘off-task’ thinking is likely to distract our focus.

In contrast to other research, though, a new study suggests the default network can sometimes help with tasks that require focus and quick reactions (Spreng et al., 2014).

Dr. Nathan Spreng, who led the research, said:

“The prevailing view is that activating brain regions referred to as the default network impairs performance on attention-demanding tasks because this network is associated with behaviors such as mind-wandering.

Our study is the first to demonstrate the opposite – that engaging the default network can also improve performance.”

Whether mind wandering helps or hinders comes down to how in sync it is with the task itself.

For example, daydreaming about an upcoming holiday is unlikely to help with solving a math puzzle.

In this study, though, people tried to match faces that were presented to them under time pressure.

The faces were either anonymous or of very famous people, like President Barack Obama.

As you’d expect, people were faster to match up the famous faces, as they’d seen them before.

But, the critical finding was that the brain’s default network — which is associated with reminiscing — supported people’s memory for these faces.

The more this area of the brain was activated, the faster they were at the task.

Dr. Spreng continued:

“Outside the laboratory, pursuing goals involves processing information filled with personal meaning – knowledge about past experiences, motivations, future plans and social context.

Our study suggests that the default network and executive control networks dynamically interact to facilitate an ongoing dialogue between the pursuit of external goals and internal meaning.”

In other words: mind wandering isn’t always bad, even when we’re trying to focus on a task that requires attention and speed.

Sometimes daydreaming helps rather than hinders.

Image credit: Xtream_I

The brain’s exercise motivation centre discovered and how it might help people with depression.

The brain’s exercise motivation centre discovered and how it might help people with depression.

The area of the brain which may control the motivation to exercise — along with other rewarding activities — has been identified by a new study.

The tiny area of the brain, called the dorsal medial habenula, was found to control mice’s motivation to exercise (Turner et al., 2014).

Since the brain structure is similar in humans and mice, it is likely that the effects on motivation and the emotions are the same.

Dr. Eric Turner, the study’s lead author, suggests the research might be the first step in developing new treatments for depression:

“Changes in physical activity and the inability to enjoy rewarding or pleasurable experiences are two hallmarks of major depression.

But the brain pathways responsible for exercise motivation have not been well understood.

Now, we can seek ways to manipulate activity within this specific area of the brain without impacting the rest of the brain’s activity.”

The study, published in the Journal of Neuroscience, used mice whose brains were genetically engineered to block signals from the dorsal medial habenula.

When compared with regular mice, the altered mice were lethargic and even took less interest in sugary drink that normal mice would have found rewarding to drink.

Dr. Turner explained:

“Without a functioning dorsal medial habenula, the mice became couch potatoes.

They were physically capable of running but appeared unmotivated to do it.”

A second study used sophisticated laser technology to allow the mice themselves to switch on or off their dorsal medial habenula by turning a wheel.

The mice much preferred to have this small part of their brains activated, thus showing it is tied to motivation and rewarding behaviour.

While it may be a long way off, the hope is that techniques can be developed to help people who are depressed ‘switch on’ their motivation and once again find pleasure in life.

Dr. Turner, who treats people with depression, concluded:

“Working in mental health can be frustrating.

We have not made a lot of progress in developing new treatments.

I hope the more we can learn about how the brain functions the more we can help people with all kinds of mental illness.”

Image credit: Banalities

This is a vital cause of low mood, poor health and lacklustre learning in teenagers.

This is a vital cause of low mood, poor health and lacklustre learning in teenagers.

Failing to get enough sleep causes low mood in teenagers, along with worse health and poor learning, a new review of the psychological evidence finds.

Although hormonal changes are partly to blame for teenage angst, being short of sleep significantly contributes to lack of motivation and poor mood.

Due to changes during puberty, teenagers require more sleep than adults and most find it hard to get to sleep before 11pm, with many staying up until 2 or 3am.

It’s not all down to late night video gaming or TV: the part of the brain which regulates the sleep-wake cycle — the Suprachiasmatic Nucleus — changes in puberty.

Teenage brains also secrete less melatonin so their ‘sleep drive’ reduces.

As a result, being forced to rise the next day at 6am for school or college means teens find it hard to get the 8 to 10 hours sleep that they need.

While educators and some parents seem to believe that teens are lazy, the problem is actually down to the adolescent biological clock.

The review of 30 years of research on this subject, published in the journal Learning, Media and Technology, finds that…

“…studies of later start times have consistently reported benefits to adolescent sleep health and learning, there [is no evidence] showing early starts have a positive impact on such things.” (Kelley et al., 2014)

Teenagers who are short of sleep consistently get worse grades in school, are more likely to be depressed and have more health problems, the research shows.

The study comes hot on the heels of calls by the American Academy of Pediatrics to delay start times to no earlier than 8:30am.

It’s not surprising: the evidence is overwhelming.

For example, one recent study, published in the Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, delayed the waking up time of adolescents at a boarding school by just 25 minutes.

They found that afterwards the number of students getting more than 8 hours sleep a night jumped from 18% to 44%.

Students experienced less daytime sleepiness, were less depressed, and found themselves using less caffeine.

Some changes in the US have already begun, with the ‘Start School Later’ campaign and the National Sleep Foundation.

The United States Air Force Academy in particular have found much improved academic results with a new late start policy introduced for their 18 and 19-year-olds.

The study’s authors conclude:

“Good policies should be based on good evidence and the data show that children are currently placed at an enormous disadvantage by being forced to keep inappropriate education times.”

Image credit: acearchie

Could violent video games make you a more caring person, at least initially?

Could violent video games make you a more caring person, at least initially?

Breaking your moral code in a virtual environment may counter-intuitively encourage more sensitivity to these kinds of violations in the real world, a new study finds.

The study, which is published in the journal Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, suggests violent video games make their players feel guilty for their moral indiscretions (Grizzard et al., 2014).

Matthew Grizzard, who led the study, said:

“Rather than leading players to become less moral, this research suggests that violent video-game play may actually lead to increased moral sensitivity.

This may, as it does in real life, provoke players to engage in voluntary behavior that benefits others.”

Participants in the study played a first-person shooter video game in one of two conditions:

“…participants in the guilt condition played as a terrorist soldier, while participants in the control condition played as a UN soldier.

The game itself informed participants of their character’s motivations to ensure that the experimenter did not bias result.” (Grizzard et al., 2014).

The researchers expected that people would feel guilty when playing the game as a terrorist, but not when they played as a peacekeeper.

Grizzard said:

“…an American who played a violent game ‘as a terrorist’ would likely consider his avatar’s unjust and violent behavior — violations of the fairness/reciprocity and harm/care domains — to be more immoral than when he or she performed the same acts in the role of a ‘UN peacekeeper.'”

Afterwards players were given tests of their moral feelings and how guilty they felt.

Grizzard explained the results:

“We found that after a subject played a violent video game, they felt guilt and that guilt was associated with greater sensitivity toward the two particular domains they violated — those of care/harm and fairness/reciprocity.”

This is not the first study to reach these conclusions.

Several studies have found that immoral virtual behaviours elicit real-world feelings of guilt — how long this guilt lasts, though, is not clear.

These studies can’t tell us what the long-term effects of these types of games are.

It may be that…

“…guilt resulting from playing as an immoral character may habituate from repeated exposures.

Under these conditions, we might expect that repeated play would not lead a gamer to become more sensitive to fairness or become more caring overall…” (Grizzard et al., 2014)

So while playing Grand Theft Auto — a game attacked for glamourising violence — may make you feel guilty the first couple of times, you may soon get used to to it.

Image credit: Steven Andrew

Join the free PsyBlog mailing list. No spam, ever.