How To Stop Obsessing Over A Dark Secret (M)

Dark secrets really do feel like a physical weight pulling downwards — here’s how to get rid of them.

Dark secrets really do feel like a physical weight pulling downwards — here’s how to get rid of them.

Intrinsic motivation is doing something for the pure pleasure of it, rather than for some external reward, such as money.

Intrinsic motivation is doing something for the pure pleasure of it, rather than for some external reward, such as money.

Intrinsic motivation, in psychology, refers to the type of motivation that comes from within.

Intrinsic motivation means doing something for its own sake and is often the healthiest and most powerful form of motivation.

In contrast, extrinsic motivation means doing something for an external reward, such as money or esteem.

Psychologists have found that while rewards can drive behaviour, they also have unexpected effects on people’s motivation.

Below are examples of intrinsic motivation, starting with a story about preschool children with much to teach all ages.

It demonstrates why rewards are sometimes not the best way to generate motivation in ourselves and others.

Psychologists Mark R. Lepper and David Greene from Stanford University and the University of Michigan were interested in testing the effects of rewards on children (Lepper et al., 1973).

Since parents so often use rewards as motivators for children they recruited fifty-one preschoolers aged between 3 and 4.

All the children selected for the study were interested in drawing.

It was crucial that they already liked drawing because Lepper and Greene wanted to see what effect rewards would have when children were already fond of the activity.

The children were then randomly assigned to one of the following conditions:

Each child was invited into a separate room to draw for 6 minutes then afterwards either given their reward or not depending on the condition.

Then, over the next few days, the children were watched through one-way mirrors to see how much they would continue drawing of their own accord.

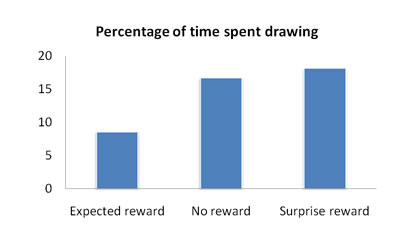

The graph below shows the percentage of time they spent drawing by experimental condition:

As you can see the expected reward had decreased the amount of spontaneous interest the children took in drawing (and there was no statistically significant difference between the no reward and surprise reward group).

So, those who had previously liked drawing (high intrinsic motivation) were less motivated once they expected to be rewarded for the activity.

In fact the expected reward reduced the amount of spontaneous drawing the children did by half.

Not only this, but judges rated the pictures drawn by the children expecting a reward as less aesthetically pleasing.

The study demonstrates both the dangers of extrinsic motivation and the power of intrinsic motivation.

It’s not only children who display this kind of reaction to rewards, though, subsequent studies have shown a similar effect on intrinsic motivation in all sorts of different populations, many of them grown-ups.

In one study, smokers who were rewarded for their efforts to quit did better at first but after three months fared worse than those given no rewards and no feedback (Curry et al., 1990).

Once again, their intrinsic motivation to give up was reduced by rewards.

Indeed those given rewards even lied more about the amount they were smoking.

Reviewing 128 studies on the effects of rewards (Deci et al., 1999) concluded that:

“…tangible rewards tend to have a substantially negative effect on intrinsic motivation (…) Even when tangible rewards are offered as indicators of good performance, they typically decrease intrinsic motivation for interesting activities.”

Rewards have even been found to make people less creative and worse at problem-solving.

Rewards, then, often undermine intrinsic motivation.

So, what’s going on?

The key to understanding these behaviours lies in the difference between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation.

When we do something for its own sake, because we enjoy it or because it fills some deep-seated desire, this is intrinsic motivation.

On the other hand when we do something because we receive some reward, like a certificate or money, this is extrinsic motivation.

The children in the study above were chosen in the first instance because they already liked drawing and they were already had intrinsic motivation to draw.

It was pleasurable, they were good at it and they got something out of it that fed their souls.

Then, some of them got a reward for drawing and their intrinsic motivation changed.

Before they had been drawing because they enjoyed it, but now it seemed as though they were drawing for the reward.

What had been intrinsic motivation, they were now being given an external, extrinsic motivation for.

This provided too much justification for what they were doing and so, paradoxically, afterwards they drew less.

This is the overjustification hypothesis for which Lepper and Greene were searching and although it seems like backwards thinking, it’s typical of the way the mind sometimes works.

We don’t just work ‘forwards’ from our attitudes and preferences to our actions, we also work ‘backwards’, working out what our attitudes and preferences must be based on our current situation, feelings or actions (see also: cognitive dissonance).

Not only this but rewards are dangerous for another reason: because they remind us of obligations, of being made to do things we don’t want to do.

Children are given rewards for eating all their food, doing their homework or tidying their bedrooms.

So, rewards become associated with painful activities that we don’t want to do.

The same goes for grown-ups: money becomes associated with work and work can be dull, tedious and painful.

When we get paid for something we automatically assume that the task is dull, tedious and painful—even when it isn’t.

That is why play can become work when we get paid and intrinsic motivation reduces.

The person who previously enjoyed painting pictures, weaving baskets, playing the cello or pretty much anything else, suddenly finds the task tedious once money has become involved.

Yes, sometimes rewards do work, especially if people really don’t want to do something.

But when tasks are inherently interesting to us rewards can damage our intrinsic motivation by undermining our natural talent for self-regulation.

Since intrinsic motivation is so powerful, it is useful to know how to increase it.

Here are some useful methods to explore for increasing intrinsic motivation for a task:

The psychological reason you should be authentic.

Positive affirmation exercises can boost confidence in the self, kickstart behaviour change, improve self-control and even IQ.

Positive affirmation exercises can boost confidence in the self, kickstart behaviour change, improve self-control and even IQ.

Positive affirmation exercises are mantras that one repeats to oneself in the hope that they will become true.

These could include self-love affirmations, affirmations for success, daily affirmations or even morning affirmations, such as:

Some people recommend positive affirmations for anxiety, depression and other mental health conditions.

While positive affirmations are often seen as merely New Age or self-help gimmicks, legitimate psychological research has found they can be effective, if used in a specific way.

The way that scientists have examined positive affirmations is in terms of ‘self-affirmations’.

Self-affirmations involve confirming or declaring one’s own personal beliefs.

For examples, have a look at the following list of values and personal characteristics.

If you had to pick just one, which most defines who you are and what matters to you?

Perhaps what matters most to you isn’t there, in that case think about what does matter to you most.

In studies on self-affirmation, participants are asked to write a paragraph or two on why this characteristic or value is so important to them.

Sometimes they also think about a specific time or story that is illustrative.

The effects can be surprisingly effective across a large number of domains.

Below are some examples of where scientists have found that positive affirmations can be useful.

Self-affirmation can boost performance for people who are put in positions of low power.

Thinking or writing about your family, your strengths or something that is important to you boosts confidence and performance.

This can even work when self-affirming or using positive affirmations about a situation which is apparently irrelevant.

Dr Sonia Kang, an organisational psychologist at the University of Toronto, who led the study, said:

“Writing down a self-affirmation may be more effective than just thinking it, but both methods can help.

Before a performance review, an employee could write or think about his best job skills.

Writing or thinking about one’s family or other positive traits that aren’t associated with the high-stakes situation also may boost confidence and performance.

Anytime you have low expectations for your performance, you tend to sink down and meet those low expectations.

Self-affirmation is a way to neutralize that threat.”

When given advice about how to change, people are often automatically defensive, trying to justify their current behaviour.

Messages about eating healthier, doing some exercise and all the rest may be rejected by stock defences, like not having enough time or energy.

But, research has found that focusing on values that are personally important — such as helping a family member — can help people act on advice they might otherwise find too threatening.

One study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, scanned people’s brains as they were given typical advice about exercise you might get from any doctor (Falk et al., 2015).

Before receiving the advice, though, some were led through a self-affirmation exercise involving positive affirmations.

This simply involves thinking about what’s important to you — it could be family, work, religion or anything that has particular meaning.

The researchers were interested in activity in part of the brain called the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (VMPFC).

The results showed that people who had used these positive affirmations beforehand displayed more activity in the VMPFC, suggesting they had taken the advice to heart.

Not only that, but their activity levels over the next month did increase more than the group who had not used positive affirmations.

For people low in social confidence, a feeling of apprehension about meeting new people is outwardly expressed as nervous behaviour and this leads to rejection.

In other words, people low in social confidence often get exactly what they expect.

However, self-affirmation or positive affirmations can help to boost social confidence, research has found.

For one study, participants looked down a list of 11 values including things like spontaneity, creativity, friends and family, personal attractiveness and so on (Stinson et al., 2011).

They put them in order of importance and wrote a couple of paragraphs saying why their top-ranked item was so important.

The results showed that this simple task boosted the relational security of insecure individuals in comparison with a control group.

Afterwards their behaviour was seen as less nervous and they reported feeling more secure.

And when they were followed up at four and eight weeks later, the benefits were still apparent.

It appears that even a task as simple as this is enough to boost the social confidence of people who feel insecure.

Failures of self-control, however, have been linked with addiction, overeating, interpersonal conflict and underachievement.

Self-control can be hard to maintain, as most of us know to our cost.

Self-affirmation, through positive affirmations, can help, though, research finds.

Some participants in one study were asked to write about their core values, e.g. their relationship with their family, their creativity or their aesthetic preferences, whatever they felt was important to them (Schmeichel & Vohs, 2009).

They were then given a classic test of self-control: submerging their hand in a bucket of icy cold water, which, if you’ve ever tried it, you’ll know becomes very painful after a minute or two.

The results showed that people who had used positive affirmations were able to hold their hand under water for more than twice as long as those who had not used a positive affirmation.

One reason positive affirmations may work is that thinking about core values puts our minds into an abstract, high-level mode.

This has been found to increase self-control.

Recalling a past success could be enough to raise IQ by 10 percent, a study has found (Hall et al., 2014).

People who were asked to use positive affirmations improved their cognitive functioning by an amount equivalent to 10 IQ points.

The study was carried out on people living in poverty.

Almost 150 people in a New Jersey soup kitchen were asked to record a personal story of a past success — this was their positive affirmation.

It was designed to see if a simple procedure could help them overcome the powerful stigma and low self-worth they were experiencing.

Professor Jiaying Zhao, who led the study, said:

“This study shows that surprisingly simple acts of self-affirmation improve the cognitive function and behavioral outcomes of people in poverty.”

A simple positive affirmation exercise can have a beneficial effect on problem-solving under stress, particularly for individuals who have been stressed recently (Cresswell et al., 2013).

Half the participants did the positive affirmation exercise while the rest performed a similar, but ineffectual exercise.

The results showed that those who had been stressed recently and were using positive affirmations before they began the exercise performed better at the problem-solving task.

This suggests that positive affirmations could be useful for people under stress who are, for example, taking exams, going to job interviews or under pressure at work.

What’s fascinating about the positive affirmations task is that it doesn’t have to be related to the area in which you’re looking to improve.

So thinking about the importance of your family can increase your problem-solving performance, even though the two have little in common.

There are even ways to boost the effect of positive affirmations.

One study has found that asking yourself a question helps boost motivation more than simple positive affirmations (Senay et al., 2010).

In other words: “Will I exercise?” works better than “I will exercise.”

In the study, one group of people told themselves they would complete an anagram task (this is a positive affirmation).

The other group, though, asked themselves whether they would complete the task.

The results showed that those who asked themselves the question solved more anagrams than those who ordered themselves.

Further experiments showed that the questioning approach helped to boost internal or ‘intrinsic’ motivation.

Psychologist have found that internal motivation is the strongest type.

It is fascinating how a simple change to language like this can help boost motivation.

Professor Dolores Albarracin, one of the study’s authors, said:

“The popular idea is that self-affirmations enhance people’s ability to meet their goals.

It seems, however, that when it comes to performing a specific behavior, asking questions is a more promising way of achieving your objectives.”

We don’t know exactly why positive affirmation exercises works, some options include that it improves people’s mood or that they engaged more with the task.

However, one likely explanation is that positive affirmations help you move your attention more flexibly, which improves memory function.

Whatever the mechanism, this growing body of evidence on the benefits of self-affirmation is encouraging.

.

Men and women respond differently to setting goals, fascinating study finds.

Men and women respond differently to setting goals, fascinating study finds.

Goals are frequently found to boost people’s motivation, and so their performance.

In the right circumstances particularly challenging goals can improve people’s performance by as much as 35 percent, a study finds.

People worked almost twice as hard when given a challenging goal compared to a more easily attainable one.

However, there is one fascinating kink in this oft-quoted research.

Men, it seems, respond to goals better than women, the study also found.

While goal-setting may work less well for women in some circumstances, it is still effective to some extent for both sexes.

Mr Samuel Smithers, the author of the research, said:

“The focus of this research was to determine how to motivate people.

When we are given a goal, we feel a sense of purpose to achieve it; it naturally helps to focus us.

The findings demonstrate that setting a goal induces higher effort.

For the study people had to do a simple addition task.

They were challenged to achieve 10 correct answers in one group and 15 correct answers in another group.

Both were compared with a control group who were given no goal.

The results showed that goal-setting had similar effects to monetary incentives.

People with goals focused more and increased their speed to complete the task.

Mr Smithers said:

“My research found that women perform better than men in the no goal setting, but men thrive in both of the goal treatments, suggesting that men are more responsive to goals than women.

I also found a 20 per cent and 35 per cent increase in correct number of additions for the medium and challenging goal groups over the control group.

This is an incredible increase in output without the need for extra monetary incentives.

The increase was due to an increase in both the speed and accuracy of the participants in the goal groups.”

The study was published in the journal Economic Letters (Smithers, 2015).

Procrastination can be overcome using these simple steps based on psychological research on how to stop procrastinating.

Procrastination can be overcome using these simple steps based on psychological research on how to stop procrastinating.

Procrastination means putting off or delaying tasks until the last minute, or sometimes even later.

Procrastination has been extensively studied by psychologists, probably because they have some world-class procrastinators close at hand: students.

Students don’t have a monopoly on procrastination, though, almost everyone procrastinates now and then.

Up to one-fifth of U.S. adults are thought to be chronic procrastinators.

The difference is that some people learn effective strategies for dealing with it and get some stuff done; others never do.

Here are ten ways to stop procrastinating and overcome procrastination, based on science:

The first tip to stop procrastination is simply to start with whatever is easy, manageable and doesn’t fill your mind with a nameless dread.

Have a look at your project, whatever it is, and decide to do the easy bit first.

The great thing is that after getting going, you start to build momentum and the harder bits are more likely to flow.

The tip relies partly on the Zeigarnik effect: the finding that unfinished tasks get stuck in the memory.

Unfinished you see: a task can’t be unfinished until it’s at least been started.

The trouble with ‘starting easy’ is that it can be difficult to know where to start: there might be several easy bits, or it might be difficult to tell what should be done and what shouldn’t.

Planning can help with this, but planning is also a trap.

Too much planning and not enough actual doing is another form of procrastination.

Take a tip from writers, artists and creatives down the ages: just start anywhere!

You may chuck away the stuff you start with, but at least it gets you into the project and helps stop procrastination.

OK, now all sorts of excuses for procrastination are crowding into your mind.

Be aware that these will come, and they’ll come big.

Here are a few of the excuses that psychologists have found people express to themselves:

Recognise some of these? You’re not alone.

This tip is all about developing an awareness that these are excuses that help perpetuate procrastination.

Be mindful of anything that’s expressed like an excuse and label it as such to help stop procrastinating.

It’s natural, but it will also stop you getting anywhere.

A massive cause of procrastination is simply not valuing the goal enough.

If we don’t care that much, we’re not going to be that motivated.

Other times the goal is unpleasant or aversive and we need to be super-motivated to do it.

Cleaning is a great example of something people often procrastinate on.

The value of this task could be increased by making a game out of it or setting time limits or unusual conditions.

For any task, though, thinking about why it’s important and trying to up its value in our minds will help stop procrastination.

Another way of cognitively increasing value is to think about the costs of not getting the task done.

Does that make the task seem more valuable?

Some people are just born procrastinators.

You know who you are.

These people are easily distracted, impulsive and have low self-control (have you even read down to number 5?).

The bad news is that you can’t change your personality (well, not much anyway).

The good news is that you can change your environment.

You can put yourself in an environment in which there are fewer distractions, temptations and all the right reinforcing signals.

Procrastination tends to strike when you have to stop and think, so have everything you need to hand and then lock yourself away.

The more you have a procrastination personality, the more the environment needs to be just right for you to get it done.

So far, so easy.

Here things get a little tricky.

That’s because when you expect a project to be difficult or hard to complete, then you are more likely to procrastinate.

But, there’s only one reliable way to increase expectations of success and that is by experiencing success.

But, while procrastinating and not starting, you can’t experience success.

It’s a Catch-22.

Hmm.

This tip is more of a warning about this Catch-22 and a reminder of that Woody Allen quote:

“80 percent of success is showing up.”

You’ve got to at least show up to find out whether you can do it.

Here are two ways of thinking about a task:

When you are feel like procrastinating, it’s much better to think about the concrete steps you are going to take, rather than abstract aims and ideas.

Thinking concrete helps you get started and stop procrastinating.

Sometimes procrastination is less an intentional thing and more about memory failures.

Most solutions to this problem are some variant of: write it down.

It may not matter that much how you make a list, or where you record the reminder — carve it into a tree if you like, as long as it’s a tree you walk past every day.

Just don’t rely on your memory to stop procrastination.

Not, at least, until you have formed a habit which doesn’t rely on memory and you start doing it automatically.

Doubts will arise for even the most confident of people.

Unfortunately, doubts cause procrastination.

Here’s a little tip for side-stepping doubts: try doubting your doubts.

One easy way to do that is by shaking your head while thinking those negative thoughts.

It may sound childish, but according to a study it can help the chronically uncertain (see: How to Fight Excessive Doubt).

There are other kinds of over-thinking which are also dangerous:

Being mindful of when we’re wasting mental energy rather than getting on with the task at hand can be useful.

These approaches will help stop procrastination

Yup, sometimes it’s just too hard, it will take too long, you really didn’t have the time, or it wasn’t worth it.

Forgive yourself.

Here’s a wonderful effect of forgiving yourself: one study has found that it can actually break you out of the cycle of procrastination (see: Procrastinate Less By Forgiving Yourself).

As the authors say:

“…forgiving oneself for procrastinating has the beneficial effect of reducing subsequent procrastination by reducing negative affect associated with the outcome of an examination.”

In other words: forgiving yourself for procrastination makes you feel better about the task, and so more likely to attempt it again in the future.

People start a task sooner when they believe it is part of their present.

So, the key to stopping procrastination is moving a task from feeling like part of the future to feeling like part of the present.

In one study, the researchers used some neat tricks to make people think a task was part of the present or part of the future.

In one, they gave some participants an assignment on the 24th of April, giving them five days to complete it.

Other participants were given the same five days to complete it, but were not given it until the 28th of April — so that the deadline fell in May.

People in the first group had the feeling the task was part of their present and so they were more likely to begin it.

Those in the second group felt it was part of May so were less likely to begin.

Remember, both groups had the same time — five days — so it was just the perception that caused some people to procrastinate.

My all time favourite procrastination quote comes from Martin Luther King, Jr.:

“You don’t have to see the whole staircase, just take the first step.”

.

Here is my quick ten-step guide to making those New Year’s resolutions, based on hundreds of psychology studies.

Here is my quick ten-step guide to making those New Year’s resolutions, based on hundreds of psychology studies.

One of the main reasons that New Year’s resolutions are so often forgotten before January is out is that they frequently require habit change.

And habits, without the right techniques, are highly resistant to change.

But because habits work unconsciously and automatically, we can tap into our in-built autopilot to get the changes we want.

So here is my quick ten-step guide to making those New Year’s resolutions, based on hundreds of psychology studies.

The classic mistake people make when choosing their New Year’s resolutions is to bite off more than they can chew.

Even with the help of psychologists, people find it hard to make relatively modest changes.

So pick something you have a reasonable chance of achieving.

You can always run the process again for another habit once the first is running smoothly.

Choosing what to change about yourself and sticking to it isn’t easy.

There is a method you can use, though, to help sort the good ideas from the bad, and to help boost your commitment.

Mental contrasting is described in more detail here but in essence it’s about contrasting the positive aspects of your change with the barriers and difficulties you’ll face.

This helps you to be more realistic about what is possible.

Research has found that following this procedure makes people more likely to give up on plans that are unrealistic but also commit more strongly to plans they can do.

The types of plans for change people make spontaneously are vague: things like: “I will be a better person” or “This year I’ll get fit”.

These are fine as overall aims but it’s much better to make really specific plans that link situations with actions.

For example, you might say to yourself: “If I feel hungry between meals, then I will eat an apple.”

When repeated these types of actions will help you achieve your overall goals.

Habits build up by repeating the same action in the same situation.

Each time you repeat it, the habit gets stronger.

The stronger it gets, the more likely you are to perform it without having to consciously will it.

So, how long will the habit take to form?

Well, it depends on both the habit you’ve chosen and your personality.

The idea that it’s always 21 days is demonstrably wrong.

Everyone is different, so what works for one person might not work for another.

Habit change is no different. If your very specific plan seems to be going wrong after a while, or doesn’t feel right, then it may need a tweak.

Try a different time of the day or performing the habit in a different way.

Habit change needs self-experimentation.

Are there any tweaks to your environment you can make?

Those trying to change eating habits might try buying smaller plates, putting fruit on the counter and avoiding TV dinners.

An odd thing happens when we try to suppress thoughts: they come back stronger.

It turns out that thought suppression is counter-productive.

The same with habits: if you try to push the thought of cake out of your mind, suddenly it will be everywhere.

Habits cannot be killed off.

It’s like the old saying that you never forget how to ride a bike.

Old habits are lying there in the back of your mind waiting to be cued off by familiar situations.

It’s much better to plan a new good habit to replace the bad old one.

Try to learn a new response to a familiar old cue.

For example, if worrying makes you bite your nails, then, when you worry, do something else with your hands, like making a hot drink, or doodling.

There’s bound to be some competition between old and new habits at first.

This is normal.

Try to notice or anticipate what the mental danger points will be and plan for them.

For example, you may want to get up earlier but know that you’ll feel lazy when you wake up.

Plan to think about something that will make you jump out of bed, like an activity you are looking forward to doing that day.

We’re most likely to give in to old habits when we’re tired, low and hungry.

So pre-commit to your new habit when your self-control is strong.

For example, clear all the unhealthy food and drink out of the house, cut up the credit card or give the gaming controller to a friend for safe-keeping.

Getting in the habit of planning ahead is one of the best ways of keeping your New Year’s resolutions.

Another trick to boost your self-control in the moment is to positive affirmations.

This involves simply thinking about something that is important to you, like your friends, family or a higher ideal.

Studies suggest this can boost depleted willpower, even when your ideas aren’t connected to the habit you are trying to ingrain.

Once you’ve successfully ingrained a modest new habit, it’s time to go back to square one, choose a new habit to work on and start again.

This is the best, most sustainable path to self re-invention—forget about waking up tomorrow a totally different person.

Instead go little-by-little, step-by-step, and eventually you will get there.

Forget all that haring around, be the tortoise.

.

The common advice to ‘find your passion’ when looking for a new career, hobby or interest could be misplaced.

The common advice to ‘find your passion’ when looking for a new career, hobby or interest could be misplaced.

Passions need to be sought out rather than just stumbled upon, research suggests.

Being open to all possibilities and taking an interest in everything that comes your way could lead to a new hobby, passion or even career.

The common advice to ‘find your passion’ when looking for a new career, hobby or interest could be misplaced.

It suggests that passions are there just waiting to be discovered.

This ‘fixed mindset’ encourages people to concentrate on their existing interests.

Instead, adopting a growth mindset helps people open up to new areas of interest.

It can also make them more likely to stick at those interests despite difficulties along the way, psychologists have found.

The study’s authors write:

“A growth theory, by contrast, leads people to express greater interest in new areas, to anticipate that pursuing interests will sometimes be challenging, and to maintain greater interest when challenges arise.”

The conclusion comes from a study in which people were encouraged to read an article that either coincided with their interests or not.

People who had a fixed mindset didn’t pay much attention to the article that was outside their interests.

However, people with a growth mindset got into the article, even though it wasn’t their usual thing.

Other tests in the same study also suggested that having a growth mindset would encouraged people to push on through barriers.

Moral of the story: take an interest in everything, you might be surprised where a new passion can come from.

Dr Paul A O’Keefe, the study’s first author, said:

“Encouraging people to develop their passion can not only promote a growth theory, but also suggests that it is an active process, not passive.

A hidden positive implication of a growth theory is the expectation that pursuing one’s interests and passions will be difficult at times because people are less likely to give up on them when faced with a challenge.”

The study was published in the journal Psychological Science (O’Keefe et al., 2018).

The key to eating healthily, reducing alcohol consumption and exercising more.

The key to eating healthily, reducing alcohol consumption and exercising more.

Visualisation is the psychological key to getting more exercise and improving diet, research finds.

Visualising eating healthily, reducing alcohol consumption and exercising more all help people change their behaviour.

The more people visualise the necessary behaviours, the more motivated they become to change.

Professor Martin Hagger, study co-author, said:

“There are strong links between chronic illnesses like heart disease and diabetes and behaviour, and imagery-based interventions offer an inexpensive, effective way of promoting healthy behaviours such as physical activity and healthy eating.

We found that people who simply visualised the steps necessary to do the healthy behaviour on a regular basis were more likely to be motivated, and actually do, the healthy behaviour.”

The researchers synthesised the results of 26 different studies to test the optimum circumstances for visualisation.

They revealed that imagery worked better when:

Professor Hagger said:

“Previous studies have shown that imagery interventions have been used in various contexts including enhancing athletes’ performance, flight simulation training for aircraft pilots and for symptom relief in hospital settings.

Our research shows that imagery is also effective for promoting participation in healthy behaviours.

Our findings may not only be of interest to health professionals around the world, but could be of interest and potentially implemented within other industries.”

The study was published in the journal Health Psychology (Conroy & Hagger, 2018).

Psychologists tested three common motivational techniques to see which works best.

Join the free PsyBlog mailing list. No spam, ever.