Happiness has two components which predict the size of this brain region.

Japanese neuroscientist have made a step forward in understanding the neurology of happiness.

They have found that happier people have a larger ‘precuneus’: an area towards the back of the brain, hidden between the two cerebral hemispheres.

The study is the first to link the area to happiness.

Researchers asked people about the two major components of happiness.

These are:

- their moment-by-moment experience of happiness,

- plus their feeling of satisfaction with life.

Positive emotions are what we naturally think of as happiness: the pleasure we get from a delicious meal or a fascinating conversation.

Satisfaction with life, though, comes more from cognitive evaluations of how well we are doing in general.

Satisfaction is less of a feeling and more of an idea or thought.

Brain scans revealed that both types of happiness were linked to larger grey matter mass in the precuneus.

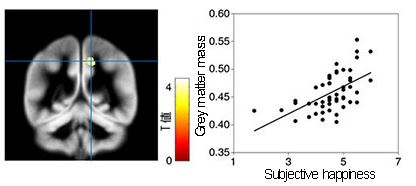

The image below on the left shows the location of the right precuneus in the brain.

The graph on the right shows the association between increasing gray matter mass in this area and increasing subjective happiness.

The precuneus has been linked to all sorts of functions, including thoughts about the self, memory and the experience of consciousness itself.

The study’s authors write:

“…our results suggest that the precuneus may play an important role in integrating different types of information and converting it into subjective happiness.”

But the study does not necessarily suggest that your level of happiness is unchangeable.

Dr Wataru Sato, who led the research, said:

“Several studies have shown that meditation increases grey matter mass in the precuneus.

This new insight on where happiness happens in the brain will be useful for developing happiness programs based on scientific research.”

The study was published in the journal Scientific Reports (Sato et al., 2015).

Happy image from Shutterstock