A classic 1931 experiment shows how the mechanics of our own problem-solving are often a puzzle to us.

The process of human creativity is both fascinating and, at the same time, mystifying. Understanding the mental processes of great thinkers offers an enormous reward to any who can replicate them: immortality. Perhaps if we really understood what was going through their minds, we too could create an object or idea that would live long after our deaths.

This idea motivated Brewster Ghiselin to collate the problem-solving processes of great thinkers and artists from Poincare to Picasso (Ghiselin, 1952). Unfortunately, as I mentioned in ‘The Hidden Workings of Our Minds‘, these great thinkers usually report being mere onlookers to their own mental processes. They seem unable to identify what prompted their discoveries and even, when they’re actually happening.

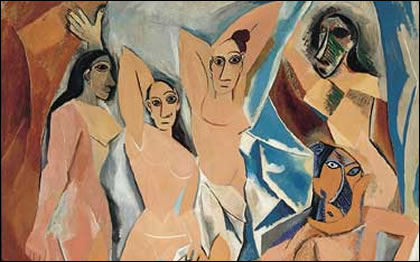

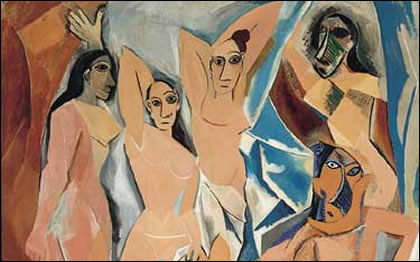

The problem is that these reports were usually made many years after the original thought processes. Picasso may simply have forgotten what prompted him to create the first ever cubist painting ‘Les Demoiselles d’Avignon’ (detail above). Perhaps if we’d asked him exactly what was going through his mind right after he painted it, the answer would have been more accurate.

A classic psychology study from 1931 suggests, though, that he still wouldn’t have been able to tell us what was going on in his mind. This experiment neatly demonstrates how we often don’t have a clue how we solve a problem.

The two cord puzzle

Way back in 1931 Norman Maier at the University of Michigan wanted to explore how people solve problems (Maier, 1931). To do this he attached two cords to the ceiling of his lab and asked people to tie the two ends together. What made it tricky was that the two cords were just far enough apart that, while holding on to one cord, you couldn’t reach the other cord.

To help participants out he placed some objects around the room which people were allowed to use. There were extension cords, poles, clamps, weights and so on. Most people worked out pretty quickly that tying an extension cord to one of the cords would solve the problem, as would using a pole. These seemingly obvious answers didn’t satisfy Maier though; he was looking for something much more simple and elegant.

So what he did was keep asking people to come up with new solutions. When they attached the extension cord, he’d say: “OK, now do it a different way.” And he kept doing this until they ran out of new solutions. Then most people just stood there, stumped.

Perhaps you can work out the solution. Remember, there are two cords. They’re just too far apart for you to reach one while holding the other one. You can use one of the items I’ve already mentioned as being in the room but you can’t bend the fundamental laws of the universe or get tricksy. So, no growing longer arms or unweaving the cord to make it longer.

Don’t read on if you’re playing along at home!

The solution

The answer, when you hear it, often provokes forehead slapping, although most people don’t get it until prompted. The answer is to attach a weight to one of the cords and set it swinging. Then you grab the other rope and can reach the swinging rope when it comes towards you.

If you got it, well done – that’s very unusual. Most people need a clue and that is what Maier eventually gave his flummoxed participants. Throughout the experiment he would be casually walking around the room until, when people had run out of solutions, he would apparently accidentally brush against one of the ropes and set it swinging.

Almost invariably people would work out the solution above in under a minute of this apparently accidental clue.

How did you solve it?

The experiment is a neat way of showing how effectively we can be primed with a solution to a problem. But the question we’re really interested in is whether we know where the solution comes from. Did Maier’s participants realise they’d been given a hint?

The answer was, on the whole, no.

When they were interviewed afterwards only one-third of his participants realised he’d given them a massive clue by setting one of the ropes swinging. Most people told some, often quite creative, stories about how they had reached the solution. These stories may well have accurately represented their conscious experience, but were clearly not the real reason why they solved the problem.

But when we take a close look at the experiment, it’s worse than that.

Fake clues

The rope swinging wasn’t the only clue that Maier used in the experiment. He had another hint which was twirling a weight on a cord. He soon found, though, that this hint was useless – it didn’t help anyone solve the puzzle. Despite this everyone who saw the dangling weight first reported that it was this that had triggered their solution not his ‘accidental’ brushing of one of the cords.

What this suggests is that even those people who identified Maier’s cord brushing as the really effective clue may have just been guessing.

The power of the unconscious

This experiment, along with others that have been conducted since, tell us that we often know little about how we solve problems, indeed generally how we think. So perhaps the best advice for how to solve problems is that provided by the great novelist Henry James, brother of the famous psychologist William James:

“I was charmed with my idea, which would take, however, much working out; and because it had so much to give, I think, must I have dropped it for the time into the deeper well of unconscious cerebration: not without the hope, doubtless, that it might eventually emerge from that reservoir, as one had already known the buried treasure to come to light, with a firm iridescent surface and a notable increase of weight” (Ghiselin, 1952, p. 26).

- The Hidden Workings of Our Minds

- Our Secret Attitude Changes

- » Why Problem Solving Itself is a Puzzle, Even to Poincare and Picasso

- What We Don’t Know About Shopping, Reading, Watching TV and Judging People

- When We Are Fools to Ourselves

- At the Heart of Attraction Lies Confusion: Choice Blindness

References

Ghiselin, B. (1952). The Creative Process: A Symposium. New American Library.

Maier, N. R. F. (1931). Reasoning in humans: II. The solution of a problem and its appearance in consciousness. Journal of Comparative Psychology, 12(2), 181-194.