Schopenhauer was such an extreme pessimist that he thought we live in the worst of all possible worlds and happiness is an illusion.

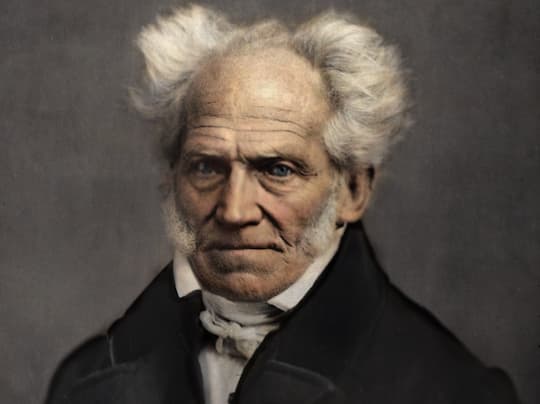

German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer was such an extreme pessimist that he thought we live in the worst of all possible worlds and happiness is an illusion.

This is what makes it surprising that he wrote a best-selling book containing a self-help section.

And yet he did.

Although calling it self-help is somewhat misleading; the main aim of his advice was really reducing misery.

Yup, old Arthur was full of fun.

Schopenhauer’s advice is interesting because it is so incredibly contrarian.

Pessimists, though, will recognise a kindred spirit when they hear his views of people and the world we live in.

Perhaps his recommendations for living have the potential to be useful for those who would normally run a mile from advice on how to be happy.

Schalkx and Bergsma (2007), in an article published in the Journal of Happiness Studies, argue that it is possible to evaluate Schopenhauer’s advice by comparing it with modern psychological findings on life satisfaction.

To do this they first examine Schopenhauer’s advice, which can be split into three parts.

First are his general rules for life, second, how we should manage our relationship with ourselves and, third, how to manage our relationships with others.

General rules for life

In short the key to making life bearable for Schopenhauer was simply this: extremely low expectations.

This piece of advice flows naturally from Schopenhauer’s philosophical position.

Like Greek philosopher Epicurus, Schopenhauer thought that happiness was the absence of pain, frustration and dissatisfaction.

He was a kind of extreme hedonist (see my post on Epicurus for the meaning of hedonism here).

We live, thought Schopenhauer, in the worst of all possible worlds, constantly on the brink of destruction.

Our will, or our desires, are continually demanding things from the world that cannot always be satisfied.

And so we are continually frustrated.

Even when our desires are satisfied it will only be brief.

This satisfaction will then lead to an increase in our desires and, ultimately, to boredom when our desires are finally exhausted.

Life, then, is suffering (an idea well-known to Buddhists).

The answer for Schopenhauer was not to seek happiness, but to try and get through life with the minimum of suffering.

His goal was for a bearable life.

Our relationship with ourselves

Here are some practical suggestions Schopenhauer put forward for managing ourselves:

- Live in the present, making it as painless as possible.

- Make good use of the only thing we can control, our own minds.

- Our personality is central to our level of happiness.

- Set limits everywhere: limits on anger, desires, wealth and power. Limitations lead to something like happiness.

- Accept misfortunes: only dwell on them if we’re responsible.

- Seek out solitude, other people rob us of our identities.

- Keep busy.

Our relationship with others

For Schopenhauer relationships with others are mainly sources of stress and hurt.

As far as he was concerned true friendship is a near impossibility.

As a result his advice is mostly aimed at protecting us from the inevitable damage other people will cause us:

- People are selfish: they are easily flattered and easily offended. Their opinions can be bought and sold for the right price. Because of this friendship is usually motivated by self-interest.

- Behaving with kindness towards others causes them to be arrogant: therefore other people must be treated with some disregard.

- Displaying your intelligence makes you incredibly unpopular: people don’t like to be reminded of their inferiority.

- Truly exceptional people prefer to be on their own because ordinary people are annoying.

- Accept that the world is filled with fools, they cannot change and neither can you.

It’s no coincidence that Schopenhauer spent 27 years living alone except for a series of poodles called Atma and Butzas as his only form of company.

(For a modern version of Schopenhauer, watch the character ‘Greg House’ in ‘House M.D.‘, or, for sci-fi buffs, Marvin the Paranoid Android).

What Schopenhauer got right

Nowadays, of course, psychological research tells us a lot more about the conditions of happiness in the modern world.

So how does Schopenhauer’s advice stack up?

Schalkx and Bergsma argue that a couple of Schopenhauer’s self-help principles do indeed stand the test of time.

1. Don’t seek wealth

Good, well done Schopenhauer, more money doesn’t necessarily equal more happiness.

2. Personality is crucial

Again, tick, well done Schopenhauer. As much as 50% of our happiness levels are genetically preset.

What Schopenhauer got wrong

Unfortunately for Schopenhauer, that’s all the good news.

The rest, when compared to modern findings, was often wrong:

1. Don’t seek status

Probably wrong. Studies often find correlations between higher status and higher levels of happiness.

2. Avoid people

Definitely wrong. Social bonds are highly correlated with happiness.

3. Don’t get married

Probably wrong.

Like Epicurus, Schopenhauer wasn’t a fan of marriage, or living with a partner.

But modern research shows that living with someone probably makes us happier – it certainly doesn’t do us any harm, on average (Bergsma, Poot & Liefbroer, 2008).

4. Avoid problems

Mostly wrong.

Setting goals and following our dreams both involve dealing with the world and overcoming problems.

Having very low expectations and avoiding trouble probably result in failing to achieve.

Research finds that goal-setting and facing and overcoming problems are associated with happiness.

Does Schopenhauer’s advice benefit the extreme pessimist?

As you’ll have gathered, Schopenhauer was the kind of chap who always thought the glass was half-empty.

Modern psychology shows that pessimism has some negative consequences, for example having lower well-being and being seen in a negative light by others.

On the other hand optimists have all sorts of advantages, like faster recovery from negative events.

But as Schopenhauer pointed out, people are different and, to a certain extent, we’re stuck with the way we are.

So while Schopenhauer’s approach might not suit the ‘average’ person, perhaps it might suit people who are like Schopenhauer?

This question is difficult to answer mainly because, in the light of modern research, Schopenhauer’s advice about being distrustful and avoiding other people is completely counter-intuitive.

Indeed, Schalkx and Bergsma argue that most of Schopenhauer’s advice probably isn’t much good, even for other people like him.

Do the opposite

Like Epicurus, though, we have to give Schopenhauer a certain amount of latitude because we are taking his advice out of its historical context.

Nevertheless when we compare his advice with modern psychology, most of it is misguided.

The few points that he does get right are mainly in the section on our relationships with ourselves.

We’re probably better off doing the exact opposite of what Schopenhauer recommends, pessimist or not.

→ Related: Confucius On Happiness: How To Live A Good Life

.