Reverse psychology is a fascinating psychological tactic that plays on human behaviour and decision-making.

What is reverse psychology?

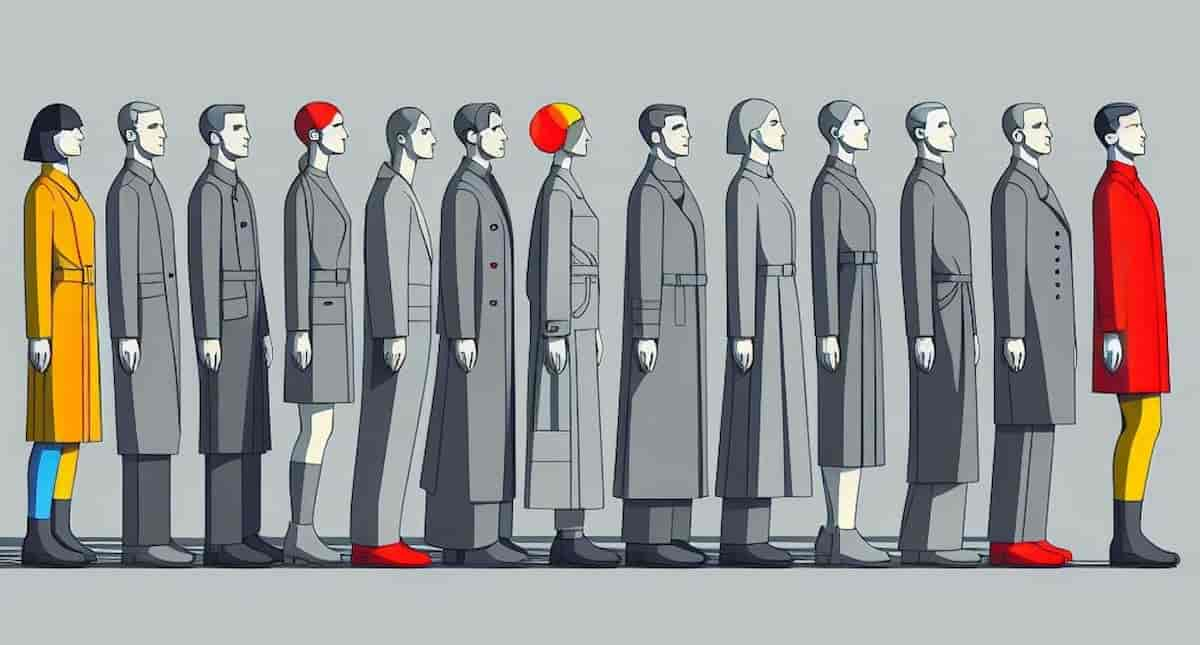

Reverse psychology refers to a communication strategy where you encourage someone to act in a way opposite to what you want, hoping they will do what you desire instead.

It relies on the principle of psychological reactance, a concept where individuals react against perceived attempts to restrict their freedom of choice.

By suggesting an opposing action, the individual may feel motivated to assert their independence and do the opposite.

Reverse psychology is frequently employed because it taps into a universal human desire for autonomy and control over choices.

How reverse psychology works

Psychological reactance, first proposed by Jack Brehm in 1966, explains the mechanics of reverse psychology.

When people sense their autonomy is threatened, they experience a motivational arousal to regain that freedom.

For example, telling someone, “You probably won’t like this movie,” may trigger a desire to prove you wrong and watch it.

This technique is particularly effective when dealing with stubborn individuals or those with a strong sense of independence.

Cognitive biases at play

Several cognitive biases contribute to the effectiveness of reverse psychology:

- Reactance bias – People resist constraints on their freedom.

- Scarcity effect – When something appears limited or restricted, it seems more valuable.

- Challenge perception – Being told they can’t do something makes individuals more determined to achieve it.

Applications of reverse psychology

Reverse psychology can be applied in various contexts to influence behaviour.

In parenting and child behaviour management

- Parents often use reverse psychology to encourage children to make desirable choices.

- For example, saying, “You probably don’t want to eat your vegetables,” might entice a child to prove otherwise by eating them.

Children, driven by a desire to assert their independence, may embrace the reverse suggestion without realising they are being guided.

In marketing and advertising

- Advertisers and marketers use reverse psychology to make products or services seem more desirable.

- Limited availability messages, such as “Only a few items left!” or “Not everyone can handle this level of spice,” can create urgency and drive demand.

Marketing campaigns often play on the perception that certain products are exclusive or not meant for everyone, increasing their allure.

In personal relationships

- It can help navigate disagreements or influence decisions by suggesting the opposite of your actual preference.

- However, using reverse psychology in relationships requires tact and understanding to avoid manipulation.

In psychotherapy and counselling

- Therapists sometimes use paradoxical interventions, a form of reverse psychology, to help clients confront their issues.

- For example, asking a client to worry more intensely can reduce anxiety by diminishing its hold over them.

Paradoxical strategies can break negative thought cycles, helping individuals see situations from new perspectives.

Effectiveness and limitations

Reverse psychology can be a powerful tool, but it is not universally effective.

Situations where it works well

- It tends to be more successful with individuals who are oppositional or independent.

- When people value autonomy and dislike direct instructions, reverse psychology can prompt desired behaviours.

In these scenarios, it plays on natural tendencies to reject control and affirm personal freedom.

Risks and ethical considerations

- Overusing or misusing reverse psychology can damage trust and relationships.

- It can be perceived as manipulative, especially if the intent is selfish or deceptive.

Building trust requires transparency, and reverse psychology used too frequently may erode credibility.

Limitations

- It may not work on highly compliant or agreeable individuals who do not exhibit strong reactance.

- In some cases, it may lead to unintended outcomes if the reverse action is taken literally.

Unpredictable results are a potential downside, making context and understanding of the individual crucial.

Strategies and techniques

Reverse psychology can be implemented using various approaches.

Common tactics

- Understatement: Downplaying the importance of something to provoke interest. For instance, “This event might be too boring for you.”

- Daring challenges: Suggesting someone can’t accomplish a task to ignite their competitive spirit.

- Feigning disinterest: Acting indifferent to an outcome to nudge someone towards pursuing it.

These methods exploit curiosity, competitiveness, and the desire to defy limits.

Examples and case studies

- A teacher might say, “You’re probably not ready for this advanced level,” encouraging students to rise to the challenge.

- A salesperson could remark, “This model may be too powerful for your needs,” stimulating curiosity and desire.

Such examples illustrate how reverse psychology subtly shifts perceptions and behaviour.

Recognising and responding to reverse psychology

Being aware of reverse psychology helps you recognise when it is being used.

- Pay attention to suggestions that seem contrary to the speaker’s goals.

- Question the intent behind statements that challenge your choices or independence.

Recognising tactics reduces their influence and helps maintain control over decisions.

Appropriate responses

- Consider whether your reaction aligns with your true intentions.

- If you suspect manipulation, take a step back to reflect on your decision-making process.

Being mindful ensures decisions reflect authentic preferences rather than reactive behaviours.

Conclusion

Reverse psychology is a fascinating and sometimes useful tool for influencing behaviour.

It leverages psychological reactance to prompt actions indirectly by suggesting the opposite.

While it can be effective, its success depends on context, personality traits, and ethical considerations.

Understanding how to use it wisely and recognising its application can help you navigate social interactions more effectively.

Moreover, learning to identify and respond appropriately allows you to maintain autonomy and make well-informed decisions, free from subtle manipulations.