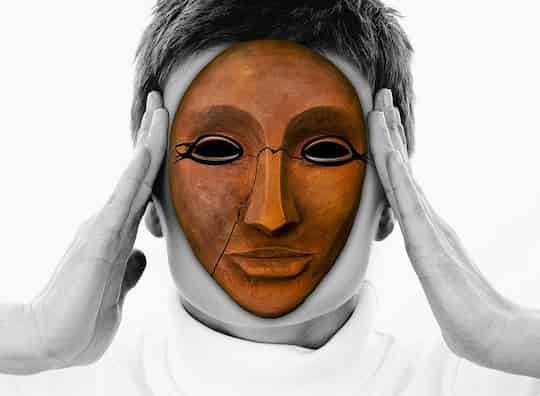

Introspection is difficult for people, which means we know surprisingly little about our own personalities, attitudes and even self-esteem.

Introspection in psychology is the process of looking inwards to examine one’s own thoughts and emotions.

Introspection is supposed to bring us self-discovery through self-reflection.

Early psychologists such as Wilhelm Wundt thought that we could research human psychology through introspection.

Wundt trained people to observe their own internal states through introspection and how they reacted to different stimuli.

However, modern psychologists have discovered that the stories we weave about our mental processes are logically appealing, but fatally flawed more often than we’d like to think.

The gulf between how we think our minds work, as accessed through introspection, and how they actually work is sometimes so huge it’s laughable.

The same finding appears again and again in many other studies demonstrating our lack of insight into who we’re attracted to, how we solve problems, where our ideas come and other areas.

Why introspection is hard

One reason that introspection is so hard is that it turns out that the unconscious is mostly inaccessible (Wilson & Dunn, 2004).

This is quite a different view of the mind than Freud had.

He thought that through introspection you could rummage around and dig things up that would help you understand yourself.

Modern theorists, though, see large parts of the mind as being completely closed off from introspection.

You can’t peer in using introspection and see what’s going on, it’s like the proverbial black box.

Types of introspection

The idea that large parts of our minds can’t be accessed is fine for basic processes like movement, seeing or hearing.

Generally, I’m not bothered to introspect about how I work out which muscles to contract to pedal my bicycle; neither do I want access to how I perceive sound.

Other types of introspection would be extremely interesting to know about.

Why do certain memories come back to me more strongly than others?

How extraverted am I really?

Why do I really vote this way rather than that?

Here are three examples of areas in which demonstrate the difficulties of introspection and why our self-knowledge is relatively low:

1. Personality and introspection

Perhaps personality is one of the best examples of how difficult introspection is.

You’d be pretty sure that you could describe your personality to someone else, right?

You know how extroverted you are, how conscientious, how optimistic?

Don’t be so sure.

When people’s personalities are measured implicitly, i.e. by seeing what they do, rather than what they say they do, the correlations are sometimes quite low (e.g. Asendorpf et al., 2002).

In other words, our lack of insight through introspection means we seem to know something about our own personalities, but not as much as we’d like to think.

2. Attitudes and introspection

Just like in personality, people’s conscious and unconscious attitudes also diverge, again making introspection difficult.

We sometimes lie about our attitudes to make ourselves look better, but this is more than that.

This difference between our conscious and unconscious attitudes occurs on subjects where we couldn’t possibly be trying to make ourselves look better (Wilson et al., 2000).

Rather, we seem to have unconscious attitudes that consciously we know little about (I’ve written about this previously in: Our secret attitude changes)

Once again we say we think one thing, but we act in a way that suggests we believe something different.

3. Self-esteem and introspection

Perhaps this is the oddest one of all and a very real challenge to the idea that accurate introspection is possible.

Surely we know how high our own self-esteem is?

Well, psychologists have used sneaky methods of measuring self-esteem indirectly and then compared them with what we explicitly say.

They’ve found only very weak connections between the two (e.g. Spalding & Hardin, 1999).

Amazingly, some studies find no connection at all.

It seems almost unbelievable that, through introspection, we aren’t aware of how high our own self-esteem is, but there it is.

It’s another serious gap between what we think we know about ourselves and what we actually know.

How to improve your self-knowledge

So, what if we want to get more accurate information about ourselves without submitting to psychological testing?

How can we introspect more accurately?

It’s not easy because according to modern theories, there is no way to directly access large parts of the unconscious mind — accurate introspection is not an option.

The only way we can find out is indirectly, by trying to piece it together from various bits of evidence we do have access to.

As you can imagine, this is a very hit-and-miss affair, which is part of the reason we find introspection so difficult.

The result of trying to piece things together is often that we end up worse off than when we started.

Take the emotions.

Studies show that when people try to use introspection to analyse the reasons for their feelings, they end up feeling less satisfied after introspecting (Wilson et al., 1993).

Focusing too much on negative feelings can make them worse and reduce our ability to find solutions.

Perhaps the best way to introspect and gain self-knowledge is to carefully watch our own thoughts and behaviour.

Ultimately, what we do is not only how others judge us but also how we should judge ourselves.

How to live with an unknowable mind

Taking all this together, here are my rough-draft principles for living with an unknowable mind that resist introspection:

- The mind is a tremendous story-teller and will try to make up pleasing stories about your thoughts and behaviour. These aren’t necessarily true.

- Using introspection you can’t always (ever?) know what you really think or who you really are.

- Using introspection to work out what you are or what you think can be damaging, encouraging rumination and depressive thoughts.

- This isn’t depressing, it’s liberating: now you know it’s perfectly normal not to understand some/most aspects of yourself, you can relax.

- If you must push for greater self-knowledge through introspection, try to become a better observer of your own thoughts and behaviour. Notice what you do and when, then try to infer the why. But don’t push it, always remember points 1-4.

.