Self-deception research in psychology suggests people find it relatively easy to pull the wool over their own eyes, when motivated.

Self-deception, meaning lying to ourselves, seems like the last thing we should do.

Surely self-deception is counter-productive and full self-awareness should be the aim?

Like calmly and deliberately shooting yourself in the foot or taking a hot toasting fork and plunging it into your eye?

But look around and it’s not hard to spot the tell-tale symptoms of self-deception in other people.

So perhaps we are also practicing self-deception ourselves in ways we can’t clearly perceive?

But is that really possible and would we really believe the lies that we ‘told’ ourselves anyway?

That’s what Quattrone & Tversky (1984) explored in a classic social psychology experiment published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.

Examples of self-deception

Any study of self-deception is going to involve a fair amount of bare-faced lying, and this research was no different.

They recruited 38 students who were told they were going to take part in a study about the “psychological and medical aspects of athletics” — no mention of self-deception.

Not true, in fact the researchers were going to trick participants into thinking that how long they could submerge their arms in cold water was diagnostic of their health status, when really it showed just how open people are to self-deception.

This is how they did it.

The experiment

The participants were first asked to plunge their arms into cold water for as long as they could.

The water was pretty cold and people could only manage this for 30 or 40 seconds.

Then, participants were given some other tasks to do to make them think they really were involved in a study about athletics.

They had a go on an exercise bike and were given a short lecture about life expectancy and how it related to the type of heart you have.

They were told there were two types of heart:

- Type I heart: associated with poorer health, shorter life expectancy and heart disease.

- Type II heart: associated with better health, longer life expectancy and low risk of heart disease.

Half were told that people with Type II hearts (apparently the ‘better’ type) have increased tolerance to cold water after exercise while the other half that it decreased tolerance to cold water.

Except, of course, this was all lies only made up to make participants think that how long they could hold their arm under water was a measure of their health, with half thinking cold-tolerance was a good sign and half thinking it was a bad sign.

Now time for the test: participants had another go at putting their arms into the cold water for as long as they could.

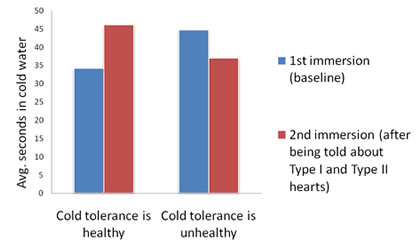

The graph below shows the average results before and after all the blatant lying (in the name of science of course!):

As you can see, the experimental manipulation had a strong effect.

People who thought it was a sign of a healthy heart to hold their arms underwater for longer did just that, while those who believed the reverse all of a sudden couldn’t take the cold.

That’s all well and good, but were these people really lying to themselves or just the experimenters and did they believe those lies?

Results of the research

After the arm-dunking each participant was asked whether they had intentionally changed the amount of time they held their arms underwater.

Of the 38 participants, 29 denied it and 9 confessed, but not directly.

Many of the 9 confessors claimed the water had changed temperature.

It hadn’t of course, this was just a way for people to justify their behaviour without directly facing their self-deception.

All the participants were then asked whether they believed they had a healthy heart or not.

Of the 29 deniers, 60 percent believed they had the healthier type of heart.

However of the confessors only 20 percent thought they had the healthier heart.

What this suggests is that the deniers were more likely to be truly practicing self-deception and not just trying to cover up their a half-truth.

They really did think that the test was telling them they had a healthy heart.

Meanwhile, the confessors tried to tell a lie back to the experimenter (seems only fair!), but privately the majority acknowledged they were practicing self-deception.

Levels of self-deception

This experiment is neat because it shows the different gradations of self-deception, all the way up to its purest form, in which people manage to trick themselves hook, line and sinker.

At this level people think and act as though their incorrect belief is completely true, totally disregarding any incoming hints from reality.

What this study suggests is that for many people self-deception is as easy as pie.

Not only will many people happily lie to themselves if given a reason, but they will only look for evidence that confirms their comforting self-deception, and then totally believe in the lies they are telling themselves.

Explains a lot, don’t you think?

.