The Stanford Prison Experiment, conducted in 1971 by psychologist Philip Zimbardo, is one of the most infamous studies in social psychology.

It revealed how power and roles can profoundly influence human behaviour.

What Was the Stanford Prison Experiment?

The Stanford Prison Experiment was designed to examine how people adapt to roles of authority and submission in a simulated prison environment.

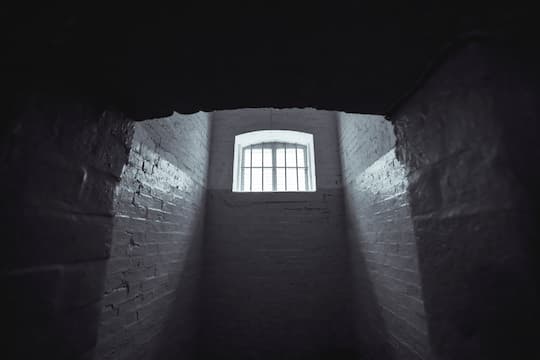

Conducted in the basement of Stanford University, the study involved 24 male college students randomly assigned as prisoners or guards.

It aimed to test the hypothesis that situational factors, rather than inherent personality traits, shape human behaviour.

Participants were paid $15 per day and were screened to ensure they were psychologically stable.

The simulated prison was equipped with cells, solitary confinement spaces, and guards’ quarters to create a realistic environment.

Zimbardo himself acted as the prison superintendent, further immersing himself in the study.

How the Experiment Unfolded

Day 1: A Quiet Beginning

The first day passed uneventfully.

Prisoners were “arrested” from their homes by actual police officers to simulate a realistic incarceration process.

They were blindfolded, stripped, and deloused to strip away their individuality.

Guards began to impose minor rules, but no serious confrontations arose.

Day 2: The First Signs of Trouble

Tensions escalated on the second day.

Prisoners barricaded themselves in their cells, refusing to comply with guards’ orders.

In response, guards used fire extinguishers to subdue them and imposed stricter punishments, such as solitary confinement.

This marked the beginning of a power dynamic where guards became increasingly authoritarian.

Day 3–5: Escalation of Abuse

By the third day, some guards displayed sadistic tendencies, devising humiliating punishments like forcing prisoners to clean toilets with their bare hands.

Prisoners began exhibiting signs of psychological distress, including emotional breakdowns and learned helplessness.

One prisoner (#8612) had to be released early due to extreme emotional distress.

Guards, emboldened by their authority, escalated their punishments, refusing bathroom access and forcing prisoners to sleep on cold floors.

Why Did the Experiment End Early?

The study was scheduled to last two weeks but was terminated after six days.

This decision followed a confrontation between Zimbardo and Christina Maslach, a graduate student who expressed shock at the guards’ behaviour and Zimbardo’s detachment.

Maslach’s intervention highlighted how deeply participants—and Zimbardo himself—had internalised their roles.

The experiment’s abrupt end prevented further psychological harm to the participants.

Ethical Controversies

The Stanford Prison Experiment is a textbook case in ethics violations in psychological research.

Issues with Consent

Although participants consented to the study, they were not fully informed about the potential risks or the extent of the emotional distress they might endure.

Some prisoners later reported feeling trapped, believing they could not leave despite assurances that participation was voluntary.

Conflict of Roles

Zimbardo’s dual role as researcher and prison superintendent blurred the line between observation and intervention.

This lack of objectivity likely contributed to the study’s escalation.

Psychological Harm

Several participants experienced lasting emotional impacts, with some reporting nightmares and anxiety long after the study ended.

The American Psychological Association later revised its ethical guidelines to prevent such harm in future research.

Critiques of the Study

The experiment has been widely criticised for its methodology and validity.

Role of the Researchers

Some researchers argue that Zimbardo and his team influenced participants, particularly the guards, by encouraging certain behaviours.

For example, evidence suggests that guards were coached to adopt harsh tactics, undermining the study’s claim to be a natural observation of behaviour.

Lack of Scientific Rigor

The small sample size and lack of a control group have been cited as significant limitations.

This raises questions about the generalisability of the findings.

Replicability

Attempts to replicate the study, such as the BBC Prison Study, have yielded different results, suggesting that the findings may not be as robust as initially thought.

The Legacy of the Experiment

Despite its controversies, the Stanford Prison Experiment remains highly influential in psychology and beyond.

Impact on Social Psychology

The study underscored the power of situational factors in shaping human behaviour, a key principle in social psychology.

It demonstrated that ordinary people could commit extraordinary acts under specific circumstances.

Connections to Real-Life Events

The experiment has been used to explain atrocities such as the abuses at Abu Ghraib prison.

Zimbardo himself testified as an expert witness in the trial of military personnel involved in the scandal, arguing that systemic factors contributed to their behaviour.

Pop Culture and Media

The experiment has inspired films, documentaries, and books, including Zimbardo’s The Lucifer Effect: Understanding How Good People Turn Evil.

A 2015 film adaptation brought the study to a wider audience, sparking renewed interest and debate.

Modern Applications and Relevance

The findings of the Stanford Prison Experiment remain relevant in discussions about power dynamics, ethics, and institutional behaviour.

Workplace and Institutional Dynamics

The study offers insights into how hierarchical systems can encourage abusive behaviours, even in corporate or educational settings.

Understanding these dynamics is crucial for creating ethical organisational cultures.

Ethics in Research

The ethical lapses in the experiment serve as a cautionary tale for researchers, emphasising the importance of protecting participants’ well-being.

Broader Lessons

The experiment challenges us to consider how we might act under similar circumstances and underscores the importance of accountability in positions of power.

Conclusion

The Stanford Prison Experiment remains a powerful, if controversial, exploration of human behaviour and the influence of authority.

Its lessons continue to resonate, reminding us of the ethical responsibilities of researchers and the profound impact of situational factors on our actions.

While its methodology and findings are debated, the experiment has undeniably shaped our understanding of psychology, power, and ethics.