The Asch conformity experiment, conducted by Solomon Asch in the 1950s, is a cornerstone of social psychology.

What was the Asch conformity experiment?

The Asch conformity experiment was designed to measure the influence of group pressure on individual judgement.

Solomon Asch set out to investigate whether individuals would conform to a group’s consensus, even when it was obviously incorrect.

This simple yet profound study demonstrated how social influence could override an individual’s perception of reality.

The setup involved groups of participants who were asked to complete a simple perceptual task.

Unbeknownst to the real participant, the other members of the group were confederates instructed to provide pre-determined, often incorrect answers.

This allowed researchers to observe how the real participant would respond to the majority’s incorrect consensus.

The methodology of the experiment

Asch’s experiment was methodologically straightforward but meticulously controlled.

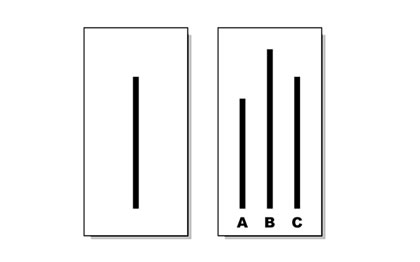

Participants were presented with two cards: one with a single vertical line and another with three lines of varying lengths.

The task was to identify which of the three lines matched the length of the single line.

While the answer was unambiguous, the majority of participants were confederates who deliberately provided incorrect answers on certain trials.

The real participant, seated towards the end of the group, heard the incorrect answers before giving their own.

This created a powerful situation in which the individual faced the choice of agreeing with the group or trusting their own judgement.

Asch conducted the experiment with multiple variations to assess the factors influencing conformity.

These included altering the group size, the unanimity of the majority, and the presence of dissenters.

Key findings and results

The results of the Asch conformity experiment revealed striking insights into human behaviour.

Approximately 75 percent of participants conformed to the incorrect majority at least once.

On average, participants conformed to the group’s incorrect response in one-third of the critical trials.

When asked why they conformed, participants provided varying explanations.

Some genuinely doubted their own perception, believing the majority to be correct.

Others knew their answers were wrong but conformed to avoid conflict or rejection.

Interestingly, when at least one other group member provided the correct answer, conformity rates significantly decreased.

This highlighted the importance of dissent in breaking the power of group pressure.

The psychology behind conformity

Several psychological factors underpinned the conformity observed in Asch’s experiment.

- Normative social influence: Participants conformed to gain acceptance or avoid disapproval from the group.

- Informational social influence: Some participants doubted their perception and assumed the group was better informed.

- Social desirability bias: Participants wanted to present themselves in a way they believed was acceptable to others.

- Group cohesion: The level of attachment to the group influenced the likelihood of conforming.

These factors are not unique to Asch’s experiment but are prevalent in everyday group dynamics.

Critiques and limitations

Despite its fascinating findings, the Asch experiment faced several criticisms.

- Ecological validity: Critics argued that the artificial nature of the experiment’s setting did not accurately reflect real-world social pressures.

- Cultural bias: The study was conducted in 1950s America, a time and culture that emphasised conformity, potentially skewing the results.

- Gender and demographic limitations: The original participants were primarily male college students, limiting the generalisability of the findings.

- Ethical concerns: Deception was used to mislead participants about the true purpose of the study, raising questions about informed consent.

Despite these critiques, the experiment remains highly influential in understanding group behaviour and social influence.

The relevance of the Asch experiment today

The findings of the Asch experiment are as relevant today as they were in the 1950s.

Modern contexts, such as social media and digital communication, amplify group influence and conformity.

The “Asch effect” can be observed in echo chambers, where individuals align their opinions with dominant group narratives to avoid conflict or ostracism.

In workplaces, groupthink can hinder creativity and lead to poor decision-making when dissenting voices are silenced.

Understanding the dynamics of conformity is essential for fostering environments that encourage critical thinking and diversity of thought.

Applications and implications

The insights from the Asch experiment have far-reaching applications across various domains.

- Education: Encouraging students to express independent thoughts can counteract the pressure to conform.

- Leadership: Leaders can create inclusive environments where dissent is valued and groupthink is minimised.

- Marketing: Advertisers use social proof to influence consumer behaviour, demonstrating the power of conformity in decision-making.

- Public policy: Recognising the impact of group influence can guide strategies to counteract harmful societal trends.

Lessons for individuals

The Asch experiment also offers valuable lessons for individuals navigating group dynamics.

- Recognise the power of group influence: Awareness of social pressures can help individuals make more informed decisions.

- Seek diverse perspectives: Engaging with a variety of viewpoints reduces the risk of falling into conformity traps.

- Cultivate independent thinking: Developing confidence in one’s judgement is a critical skill in resisting undue influence.

- Encourage dissent: Supporting those who voice minority opinions can break the cycle of conformity.

Conclusion

The Asch conformity experiment remains a landmark study in social psychology, shedding light on the powerful influence of group pressure.

While the findings revealed human susceptibility to conformity, they also underscored the importance of independent thinking and dissent.

In today’s interconnected world, where social and digital influences are pervasive, the lessons from Asch’s work are more relevant than ever.

By understanding and addressing the dynamics of conformity, we can foster environments that value individuality and critical thought.